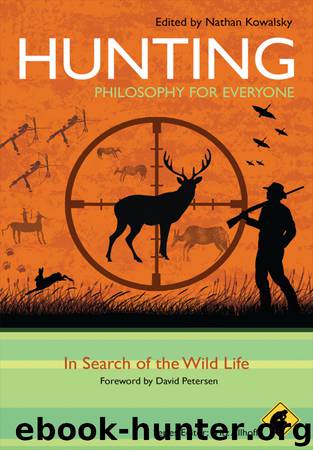

Hunting - Philosophy for Everyone by Kowalsky Nathan Allhoff Fritz Petersen David

Author:Kowalsky, Nathan, Allhoff, Fritz, Petersen, David

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Published: 2010-11-04T04:00:00+00:00

JANINA DUERR

CHAPTER 11

THE FEAR OF THE LORD

Hunting as if the Boss is Watching

You see what we object to in this spirit is that one side of him is rotting and putrefying, the other side sound and healthy, and it all depends on which side of him you touch whether you see the dawn again or no.1

Nothing Wants to Die

Most people like meat and value hunting, which is almost universally considered a prestigious affair. Yet hunters commonly perceive that animals love to live and do not want to die, as they might scream, express pain, and attempt to escape. At the very least, animals normally do not grant the humans permission to kill them, leaving the hunter in a position of debt. This is reflected in the common belief that “the stealing of a life calls for a life in return.”2 The most straightforward response to this ethical principle would be for the hunter to give his own life – not very tantalizing, and in the end, useful only once – or, alternatively, to give something with a value equivalent to the life of the animal. As this exchange does not always take place, hunting is often understood as unethical, an asymmetric relationship between game and hunter. This dilemma between the drive for killing and the bad feelings associated with it has been termed Tiertöterskrupulantismus (the experience of scruples about the killing of animals) by Rudolf Bilz and he identified it as a universal psychological principle.3 All over the world hunters show scruples when killing animals and are ridden by guilt after the hunt.4 This is expressed in moral sentiments, hunting habits, and in myths: South African G/wi were certain that antelopes hated them since God had told the antelopes that human fires were used for cooking them.5 The Chenchu of Southern India told a myth where animals came together to discuss how best they could avoid being caught and slaughtered.6

Predation becomes all the more objectionable when animals are considered to be human-like, social beings capable of emotions: a hunter chases game that, in another world, has a family waiting. The Algonquins, for example, believed that animals could talk and think and were only outwardly different from humans.7 The Huaulu of the Moluccas were convinced that animals lived in subterranean buildings that looked like human houses and had mattiulu, a soul or animating principle,8 just as the Latin word “animal” derives from anima, “soul.” Iglulik Eskimo9 felt bad because they had to kill animals which had souls.10 Such conceptions result in a fear of retaliation: Navaho hunters refused to bring home a deer if the dying animal gave a warning shout.11 Tapirs passing by a grill could recognize the traces of the slaughter of one of their kind and would try to roast the Aparai hunters in French Guiana in revenge.12

An Eye for an Eye, a Tooth for a Tooth

To make matters worse, most wild game is protected by a mythical figure, the Master or Mistress of Animals. This designation derives

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7354)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7137)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6800)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6621)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5790)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5519)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5196)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4455)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4312)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4279)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4262)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4257)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4133)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4012)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3969)